In our workplace dictionary, “a crowded room” and “dead silence” might not exactly be antonyms. On numerous occasions, you might find yourself in a meeting, surrounded by a handful of colleagues. A simple question of “does anyone have any objection?” is raised to your audiences, and you wait. Still, no one accepts the invitation to opine. Eventually, the head of the meeting has to take it upon themself to wrap up the meeting. This temporary moment of awkwardness repeats itself, over and over, until you lose count of how many times it happens.

Or sometimes the unspoken lingers in daily interactions. A senior staff utters a word that you believe would definitely spark contretemps in the office. Tension hangs heavy in the air. You see disapproving looks on many faces, lips pursed tightly, not a single sign of agreement on sight. Yet no one dares raise a hand and speak their mind. Those who open their mouths only try to laugh it off, directing a discussion to an entirely new trajectory.

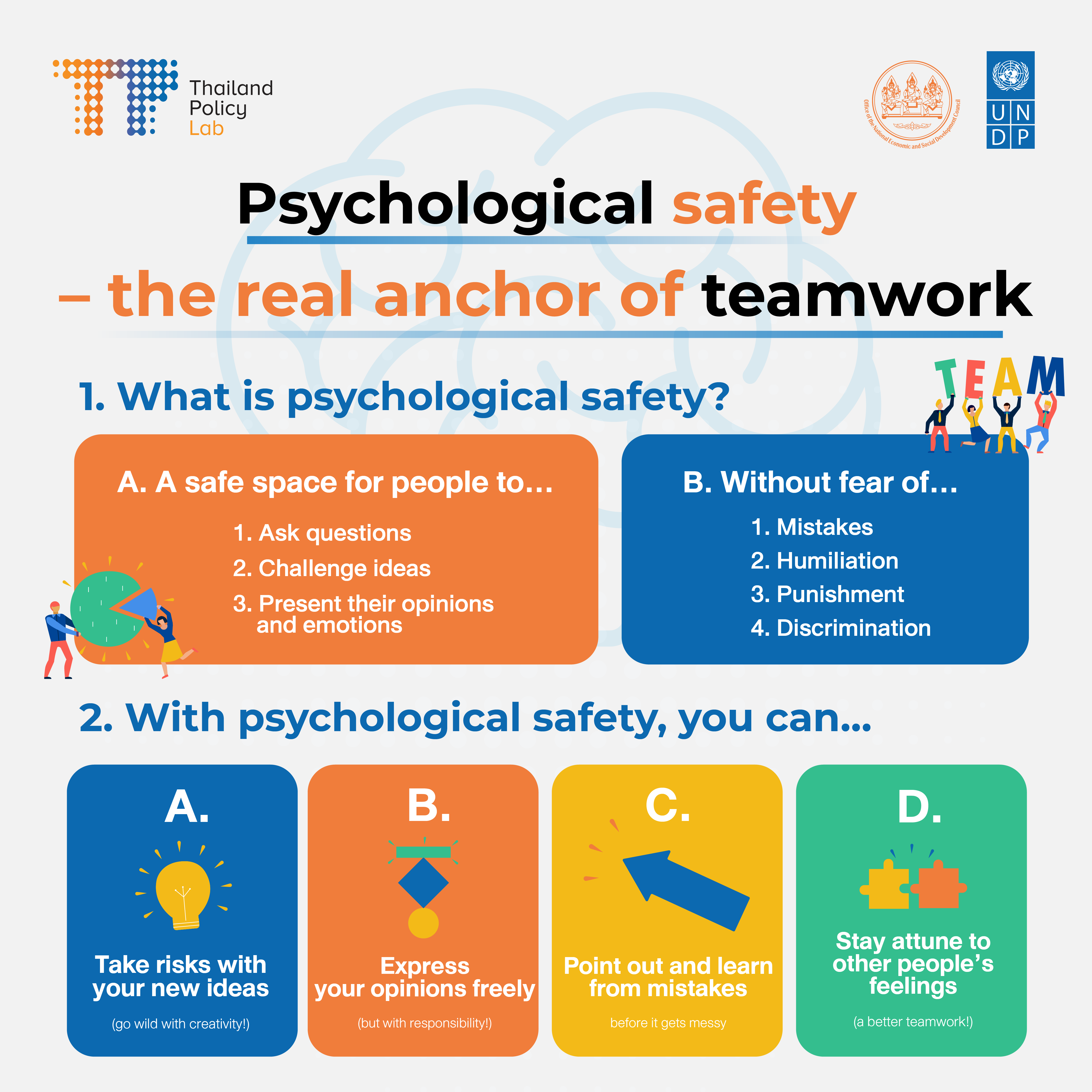

What happens in those instances bear symptoms of “psychological safety” deficiency, or lack of trust and sense of security when expressing opinions among colleagues. Psychological safety is all about providing a space for another person to ask questions, challenge, and propose ideas without fear of mistakes, humiliation, punishment, dismissal, or discrimination. Without it, constructive criticism will not take roots in our organisational culture.

Why don’t people feel safe in the first place? Let’s take a look at this psychological safety deficient work culture checklist.

Several causes are behind this evasive stance to workplace conflicts or even simple opinion-sharing. It could be…

1. Discrimination in workplace

Discrimination based on personal characteristics – such as age, gender, and ethnicity – plays a significant role in hambering conversations. Historically, members of the marginalised communities are subjected to rejection and mistreatment in a biassed environment, resulting in social exclusion, the first step towards issues that are even more severe than oppressed opinions, such as eventual resignation and mistreated workers’ economic precarity.

The violence of discrimination has a varying degree; it needs not to be physical abuse or explicit vitriols targeting specific individuals. Each day, marginalised people are met with what we call “microaggressions,” or actions with a subtle hint of discrimination. It could be sexist remarks about women’s “hysteria” and “irrationality” when expressing opinions with strong feelings, or women’s “lack of charismatic leadership” when heading a meeting. Biassed assumptions, insensitive speech, or problematic stereotypes might secretly slip our consciousness, and end the conversation we are supposed to have with our colleagues even before we know it.

2. Bureaucratic Red Rape

A long list of regulations is a two-edged sword. Although they are put in place to preempt errors in administrative procedures, these institutional safeguards can create a massive bottleneck for decision making. This situation is otherwise known as Red Tape. One of the byproducts of this overly rigid adherence to excessive formal rules is a work culture that treats staff as just another cog in the machine. Workers are conditioned to simply comply with regulations, and anything that strays from the convention and rules is deemed inappropriate. This could create a mentality that fears flexibility and germinates resistance to creativity.

3. The “you scratched my back, I’ll scratch yours” attitude in the office

Deeply ingrained in many professional realms, the patron-client system is one of the most notable factors for all the deliberately calculated silence. We all know the game of organising workplace relationships, in which some staff members focus their efforts on appeasing, and gaining favour from, one’s superiors. It naturally harbours myriads of cliques that are busy climbing the social-professional ladder. Instead of striving for result-based efficiency or maintaining ethical standards, the competition revolves around tug-of-wars for power.

4. The seniority system and paternalism

In many Asian countries, paternalistic values lay the foundation for the governance of human relations. As the saying goes, “the youth can walk fast, but the elder knows the road.” We are taught to respect leading seniors by showing no sign of contention. We should follow their decisions, and trust their judgments under any circumstances.

Contrary to Red Tape, a paternalistic environment does not always have an air of formality or overt oppression. Mutual generosity and a sense of kinship are often the glue that binds the organisation together. However, the seniority system can still put up an invisible wall for junior staff who wish to enter into debates with their seniors, as criticisms can be considered as both defiance and a personal attack, disrupting the interpersonal relations between workers and souring the “pleasant” work environment.

What could be antidotes to psychological safety deficiency?

1. Leadership’s commitment to organisational change

Donald and Charles Sull, experts on corporate culture, observed that an unhealthy work culture was allowed to exist mostly because leadership refused to invest in change. In essence, work culture issues are also leadership’s issues. To lead an organisation is to make sure that staff thrive in a healthy environment, with a constructive feedback culture that does not give carte blanche to discriminatory speech.

Sull suggested that the importance and benefits of cultural detox should be put on the forefront of the agenda, highlighting the urgency of the issue to all parties involved so that everyone could be on the same page. For psychological safety, their benefits are not merely additional advantages to workers, but fundamental to us as human beings. The researchers of Google’s Project Aristotle, a project that tackled teamwork improvement, found that psychological safety made the workplace a fulfilling and relaxing environment for workers. They felt at ease enough to expand their horizons by taking risks with new ideas. They also began to express their opinions in its full breadth – even if the necessary conversation might not be an easy one, such as pointing errors or the cause of their discomfort. This helped the entire learn about each other better, and correct the wrongs done to other parties.

Another piece of advice from Sull was to put external pressure on the organisation. Public reports on the organisation’s progress could keep psychological safety atop leadership’s agenda, as it reveals how the organisation treats their staff.

2. Adopt Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion (DEI) strategy

In many cases, the sense of insecurity derives from the environment that tolerates discrimination. It is crucial that organisations take diversity, equity, and inclusion seriously. We must bear in mind that DEI is not about pushing marginalised people towards the stage to take the microphone, revealing their most vulnerable moments to the entire world when they might not be ready. In essence, the goal of DEI is to…

- Ensure equal representation and opportunities for marginalised people

- Provide needed resources and support

- Make sure that people feel as if they belong there.

That means that we cannot count social justice out of organisational core values. It is crucial that we take a conversation about “progress” beyond the fables of productivity and efficiency. Leadership must promote a culture of accountability, with grievance mechanisms to address harms and reparations. On a smaller scale, it also means encouraging staff to approach their colleagues with sensitivity and willingness to take responsibility for their offences.