In the policy learning field, academics, policy makers and decision makers tend to focus on policy “success.” That sort of focus is seen as advantageous since success is value-laden with the thought that if we study success, it translates to our own success. Lying behind learning about policy success is the assumption that we may be able to replicate successful policies, scale them up, and succeed in the same way. This is perhaps why we focus the attention on learning all those “best practices.”

In other words, we are inclined to pay attention to ‘success’ and not ‘failure.’

In fact, failures do happen many times more often than successes and those best practices are not something readily replicable. Behind a successful case are a myriad of variables, the social and cultural contexts, politics, and people. Learning about policy success in one context cannot be easily translated into another context.

Learning about successes is not inherently beneficial. Successful cases may not be the answer to improved policymaking. We only learn superficially, if we only look at those successes.

Ching Leong and Michael Howlett, public policy scholars, say that policy makers should also focus on the ‘dark sides’ of public policy and this has to be profoundly studied in order to mitigate policy failures. Learning about policy successes tends to assume that policy makers and stakeholders are good-intentioned and always work towards policy improvement and achievement; however, such a focus overlooks the facts that policy makers have their own interests, too. Sometimes policy makers can have malicious intentions and their own interests do not always align with public interests. Think about civil officers who do not want to adapt to new things, do not want to work harder, or even side with political groups that work against the government and pull political manoeuvres, all of this can lead to policy failures.

Learning about policy success or the ‘bright sides’ that focuses on enhancing efficiency and fixing mistakes thus overlooks the ‘dark sides’ or one of the most essential elements that lead to policy success: relationship management, interest management, and malicious intention mitigation.

In the public policy academia, there have been studies that pay attention to the malicious intentions and personal interests of stakeholders. Such concepts are, for instance,

- Game theory – Stakeholders make decisions based on the assumption about other people’s decisions, in order to achieve their best interests. The results are often suboptimal outcomes as a consequence of such complex interactions.

- Free-ridership – Stakeholders do not want to work hard but desire to free-ride or rake in other people’s hard work.

- Rent seeking – Stakeholders lobby the government or the authorities to seek interests from existing systems as if setting higher rent fees while the property remains unchanged. It is to seek wealth from the system as it is without creating new wealth, in other words, to exploit people.

Learning about policy lessons should study these aforementioned behaviours. To improve policy making, there is a need to “profoundly” learn about personal interests to mitigate risks and failures rather than just learning about successes that, more often than not, do not discuss surrounding contexts and human dimensions.

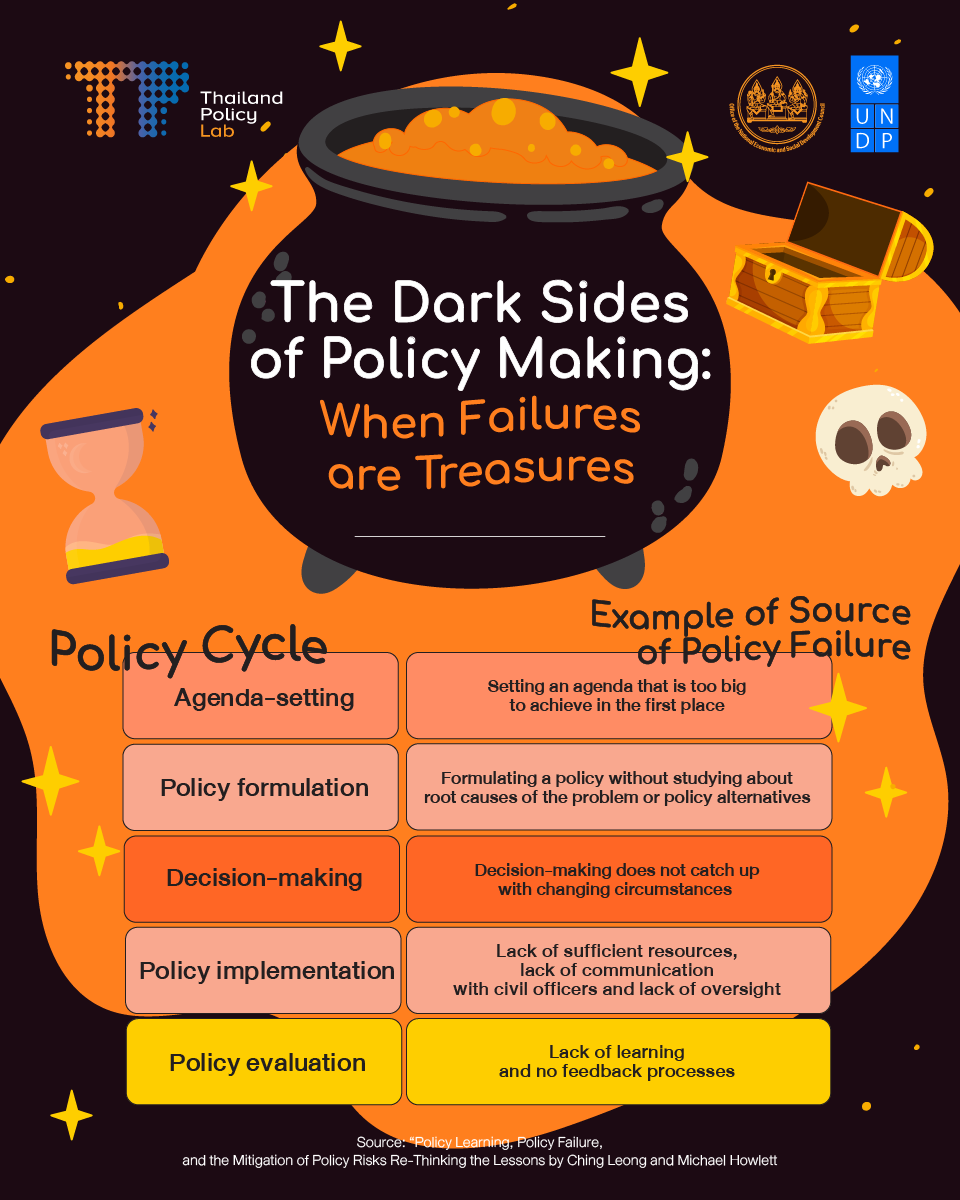

Policy makers can try to learn more about failures. One of the ways by which policy makers can do that is to analyse the risks of failures in each policy cycle, to see when failures can happen, at which stage, and why.

| Policy Cycle | Example of Source of Policy Failure |

| Agenda-setting | Setting an agenda that is too big to achieve in the first place |

| Policy formulation | Formulating a policy without studying about root causes of the problem or policy alternatives |

| Decision-making | Decision-making does not catch up with changing circumstances or distort policy intentions by bargaining and log-rolling |

| Policy implementation | Lack of sufficient resources, lack of communication with civil officers, and oversight |

| Policy evaluation | Lack of learning and no feedback processes |

Seeing “failures as treasures” can benefit policy making more than one could ever know.

Learning only about successes can deviate attention from the variables such as personal interests that do not align with public interests which lead to policy failures in several cases. Seeing possible failures in each stage of the policy cycle can shed light on the human dimensions, rendering the analysis of the “dark sides” of policy making more effective. In a nutshell, learning about failures can lead to success as well.